Wednesday, August 19, 2015

Monday, August 17, 2015

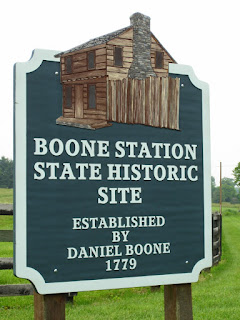

Boone Station

The Colonel and I were driving along the modern version of Boone's Trace as were made our way to our next stop, Boone Station State Historical Site.A dark, wooden fence now encloses what was once the site of Boone Station.

Daniel Boone surveyed this site in 1774 for a 4,000-acre land grant to James Hickman. In December 1779, Boone and other families lived here in crude shelters. In 1780, they built cabins and a stockade in an area of about half an acre. There was a well inside Boone Station but water was also available from a spring located downhill from the station. By 1783, the station included about 15 to 20 families. Among these were Boone's brother Edward, son Israel and nephew Thomas who were killed in the final battle of the American Revolutionary War at Blue Licks.

Daniel Boone occupied the station until 1784 and his sister's family was there until 1814.

The spring used by those living at Boone Station

In 1795, Robert Frank bought the land and buildings of Boone Station and built his two-story stone mansion which lasted into the 1800s. In 1991, Robert C. Strader willed some 47 acres, including the site of the station to the state of Kentucky. Boone Station State Park opened in 1992.

Excavations by the University of Kentucky uncovered stone foundations of station cabins, and a short section of the stockade ditch built by the Boones. The 1780 station cabins varied in size. Each had a chimney and fireplace at one end. The large stone foundations of the 1795 Frank house were discovered also. The Frank house was built on the same alignment as the Boone cabins. The stockade was no longer needed and was torn down by Robert Frank but the station's cabins were useful to Frank's house slaves and other purposes. Frank's house had a chimney on each end as well as a deep cellar.

The Colonel and I saw no remnants of the former buildings of Boone Station or Robert Frank's house. There are only an interpretive board about the U of K excavation and a granite marker (see it in the distance) that stands where some of the Boones are buried.

We were not far from what would be the next stop on our "All Things Boone" trip back to Florida, Fort Boonesborough, but it was getting late and we needed to find a hotel for the night. We would "attack" the fort the next day.

Saturday, August 15, 2015

Millersburg to Paris

Blue Licks was now behind us and we were heading towards Lexington, Kentucky. Along the way we encountered a very old cemetery that begged to be explored.

There were two sections to this interesting cemetery: a larger open area and a smaller area that was surrounded by a stone fence.

We saw a tall headstone nearly lost in a tangle of vegetation.

Upon closer inspection, we saw that it was the grave marker for Major John Miller (1752-1815), a Revolutionary War soldier and the founder of Millersburg, Kentucky.

Major John Miller founded Millersburg in 1817. He was one of the earliest settlers in Bourbon County. He was born in Pennsylvania and came to Kentucky in 1775. He was granted 400 acres of land by the Governor of Virginia (the land that was to become Kentucky was considered part of Virginia at the time). Major Miller bought an additional 1,000 acres at 20 shillings per 100 acres.

While he was surveying his land he was continually menaced by Indians so Major Miller built a block house or fort. He also planted corn during this time.

In 1798, Major John Miller surveyed 100 acres, laid out in-town lots and incorporated his new town of Millersburg.

Millersburg would eventually have flour mills, linsey-wool and flax cloth mills as well as shops that would manufacture spinning wheels and furniture. Farm produce from Millersburg would be shipped on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to New Orleans.

It was said that Major John Miller was a man of fine intellectual and physical powers. He and his wife, Ann McClintock Miller would have four sons and two daughters. Ann is buried next to her husband.

The 2010 census listed 792 persons living in Millersburg, Kentucky. Looking at the historical data for the population, Millersburg has always been a small town.

As The Colonel and I walked among the headstones we spied the only mausoleum in the old cemetery. It was very intriguing. It looked a bit like a tiny castle that had barely withstood bombardment.

We walked around the structure and saw the subterranean entrance (barely large enough for an adult to squeeze through, they must have built the mausoleum around the interred). I was so tempted to stick my camera in the entrance and snap a couple of photos, but I was too chicken. We did see evidence of visits to/in the structure by way of discarded beer cans.

We saw this marble marker lying on the ground near the mausoleum.

The marker reads: Louisa Snow, 2nd wife of Aquilla Willet, aged __ years.

When we were back in Florida we did some research on the Internet and learned more about Aquilla Willet and his two wives.

Aquilla Willet died on September 29, 1843 at the age of 55. He was the first blacksmith in Bourbon County. In 1841, he was appointed U.S. Postmaster for Millersburg, Bourbon County, Kentucky. He married his first wife, Electra Francina Wilder Lane in 1837. Electra would die in 1839. (I love these names...Aquilla and Electra).

In April of 1843, Aquilla married his second wife, Louisa Snow. Aquilla would be dead by September of that same year.

There is no age of death listed on Louisa Snow's marble marker that is because she is not buried in the Willet mausoleum (perhaps Aquilla had it built when his first wife died).

Louisa Snow Willet was a true pioneer woman. She was born in Maine, married Aquilla in Ohio, moved to Kentucky with him but upon his death moved ever westward. In 1900, Louisa lived in San Diego, California. She died in 1907 at the age of 94. What a life she must have lived and what things she must have seen. She lived from coast to coast, Maine to California.

All the tromping around toe stones and headstones made The Colonel and I hungry, so we got back into the car and hit the road to Lexington, Kentucky.

Between Millersburg and Lexington was Paris (The Thoroughbred Capital of the World). I popped into Paris, Kentucky's visitor center to inquire as to where The Colonel and I might enjoy a nice lunch. I was immediately welcomed by a handful of middle-aged ladies who were stuffing visitor's bags. They gave me one as they told me about a nice little restaurant around the corner. In my bag was a key chain, a little bag of Bluegrass seed and several brochures about area attractions. I thanked the friendly ladies and headed back to the waiting Colonel.

We found our lunch destination...Lil's Coffee House...and a parking spot just across the street.

Lil's little lunch counter was situated along the left wall as you walked through the double doors and to the right, across from the counter, was a huge space filled with antiques.

The Colonel and I were the only ones seated at the lunch counter. Our very friendly waitress served us well and we got our delicious lunches quickly. We had the tortilla soup and then I had the quiche and The Colonel had a sandwich of some kind.

I loved the pretty plate my lunch was served on.

Our waitress asked us where we were from and when we were ready to settle our bill she told us to have a good and safe trip back to Florida. The Colonel and I decided that a trip back to Paris would not be out of the question.

Our bellies were comfortably full and it was time to get back on the road to Lexington and leave the Thoroughbred Capital of the World behind.

Monday, August 3, 2015

Blue Licks

The Colonel and I were now beginning our descent into the heart of Kentucky's "Boone Country". We had left Daniel and Rebecca Boone's mortal remains behind us and were making our way to parts of Kentucky that still vibrated with the energies of the Boone legacy.

Our next stop was at Blue Licks Battlefield State Park.

The Battle at Blue Licks is considered the last battle of the American Revolutionary War. It took place ten months after Lord Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, Virginia.

On August 15, 1782, Shawnee Indians, under the orders of British Captain William Caldwell and with the help of Simon Girty (a liaison between the British and their Indian allies), planned a surprise attack on Bryan Station, an early fortified settlement near Lexington, Kentucky, established 1775-76 by four Bryan brothers from North Carolina. The defenders of the station learned of the attack beforehand and were ready to repel the Indians.

The women of the station were asked to go outside of the stockade walls to get water from the spring nearby. These very brave women were to act like it was a normal day and pretend that they knew nothing of the Indians who were watching them from the woods. The Shawnee had no reservations when it came to killing women and children.

The Heroines of Bryan Station Fort

Original watercolor by Emily Utterf,

Bryan Station Chapter Member

The women were able to fill their water buckets and return within the safety of the walls of Bryan Station.

For two days the Shawnee attacked the station. They killed five white settlers and wounded two more before retreating toward the Ohio River.

Upon hearing of the attack on Bryan Station, Kentucky pioneers, Daniel Boone and his son Israel among them, were inclined to pursuing the enemy. Daniel Boone was in favor of waiting for reinforcements before beginning the pursuit.

On August 19, 1782, although under the general leadership of Major John Todd, Major Hugh McGary, eager to prove he was no coward, urged immediate pursuit and attack of the enemy. When no one heeded him, he mounted his horse and rode across the ford and yelled, "Them that aint cowards follow me." The men followed, as did the officers, who hoped to restore order. Daniel Boone was suspicious of the obvious trail left by the Indians thinking it would lead them into an ambush. Boone remarked, "We are all slaughtered men," and crossed the river.

The Kentucky pioneers suffered a bitter defeat and were routed by their Revolutionary War enemies. Captain Caldwell concealed his British and Indian army along the ravines leading from the hilltop to the Licking River. Advancing into this ambush, the pioneers were out-numbered and forced to flee across the river. Daniel Boone's 23 year-old son, Israel, was shot in the neck and killed during the retreat. Sixty of the 176 men who followed McGary were killed and another seven were captured. Reinforcements under George Rogers Clark (my buddy comes through once again) eventually arrived and drove Caldwell's forces from Kentucky for good.

At the Blue Licks Battlefield State Park is an impressive monument that honors those who fought and/or died during the battle.

The Colonel and I walked down the stone steps that lead to the monument. Along the way there was a little raised bed of soil. It is here that the martyrs of the last battle of the American Revolution are buried.

We continued down the steps to the tall monument.

The monument was engraved with the names of those who bravely fought in the battle.

"Enough of honour cannot be paid" - Daniel Boone

There was a fireplace ruin on the grounds of the state park. It was set upon a hilltop.

An historic marker nearby informed us that these were what remained of the home and grave (we never did see where that was) of Major George M. Bedinger (1756-1843). He was an officer in the American Revolutionary War in defense of Boonesborough in 1779 and at the siege of Yorktown in 1781. He came to Kentucky in 1784, first to survey the area and to fight in the Indian campaign in 1791. Major Bedinger was a Kentucky legislator (1792-94), and a U.S. congressman (1803-07). He opposed slavery and freed his slaves when they turned 30 years old (seems a bit long to keep your slaves in bondage especially when you claim you are against slavery...just saying).

The Blue Licks Battlefield State Park is home to a 15-acre state nature preserve. It contains a cedar glade that was previously an open area that was once used by a large number of herbivores such as Bison, Elk and even Woolly Mammoths. Today the glade is a forest that is home to the federally endangered Short's Goldenrod and the state threatened Great Plains Ladies'-Tresses (images from the Internet).

The Colonel and I did not see these plants while we were at the park (due to poor website content as we researched for our trip, as well as very poor signage and the lack of an available ranger within the park).

We had much more to see and do in Kentucky, so we got back into our car and began to make our way towards Lexington and more Boone history.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)